- Home

- Elena Passarello

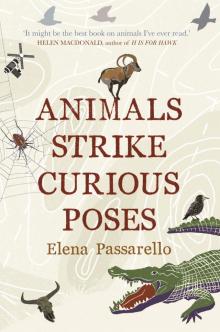

Animals Strike Curious Poses

Animals Strike Curious Poses Read online

Contents

Cover

About the Book

About the Author

Dedication

Title Page

Epigraph

Yuka (39,000 BP)

The Wolf of Gubbio (1207)

Ganda (1515)

Sackerson (1601)

Jeoffry (1760)

Vogel Staar (1784)

Harriet (1835)

War Pigs (1870-2012)

Jumbo II (1901)

Four Horsemen (1904-2012)

Mike (1945)

Arabella (1973)

Lancelot (1985)

Koko (1988)

Osama (1998)

Celia (2003)

Cecil (2015)

Notes

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Copyright

About the Book

In this remarkable collection of essays Elena Passarello traces the stories of famous animals named and immortalised by humans, from Yuka, a 39,000-year-old woolly mammoth recently found in the Siberian permafrost, to Charles Darwin’s tortoise Harriet, a deformed goat who was billed as ‘Lancelot, the Living Unicorn’ by Ringling Bros Circus in 1985, and Cecil the Lion, shot in 2015 by an American dentist out big-game hunting. Throughout, Passarello startles us with her wit, her invention and her curiosity.

About the Author

Elena Passarello is an actor, a writer, and recipient of a 2015 Whiting Award. Her first collection, Let Me Clear My Throat, won the gold medal for non-fiction at the 2013 Independent Publisher Awards and was a finalist for the 2014 Oregon Book Award. Her essays on performance, pop culture and the natural world have been published in Oxford American, Slate, Creative Nonfiction and the Iowa Review, among other publications. Passarello lives in Corvallis, Oregon and teaches at Oregon State University.

For Pizza Rat.

Just kidding. For David.

Year by year,

the monkey’s mask

reveals the monkey.

—Bashō

Even more interesting, there are hints that humans may have taken over the kill at an early stage.

Professor Daniel Fisher, 2012

They have been here!

Eliette Brunel in Chauvet Cave, 1994

HE FOUND THE mammoth in the rock-hard earth.

She lay at the top of the continent, near a sea that thaws in July and refreezes by September. It was a tusk hunter who spotted her, upside-down, in the half-frozen crag. First a rock, then a rock in the shape of a foot and a flank and a hollowed-out eye. Her trunk extended down the crag like a pull-chain.

Quickly, he could see that, as if by some ancient magic, she was still woolly. Red-blonde fetlocks clung to her feet, her haunches, to the rock that kept her. It was thick and vibrant, the kind you’d see on a ginger-haired dime-store doll. The hunter who chiseled her from the permafrost—we think he was named Vasily—kept quiet about his process, but no matter the work, it was too easy a task. Cutting away thirty-nine thousand years should cost a monument of labor. Instead, as payment, he pushed a silver earring into the thawing silt.

The rock that had kept her for millennia was four days’ journey from anything road-like, so Vasily assembled a posse, tied her to a snowmobile, and got down to it. The summer thaw did little to speed their sledge from Yukagir toward the mountains, and somewhere between the Laptev Sea and the village of Ust-Kuyga, she thawed a bit, loosening to the temperature of the living for about three days. They finally parked the slab he’d dragged her on, still nine hundred miles north of the coldest city on the planet, in an undisclosed ice cave: sped from one frozen home to another to await the highest bidder.

Vasily and company figured that any twenty-first-century human—science-mole, ivory-hawk, or adventure-hound—once he crawled into the cave and pulled back the blue tarps that swaddled her? He’d bite at the first sight of that Pleistocene wool. Because uncovering a mammoth in a frozen cave does something to a neocortex. Since language is epically younger than both thought and experience, “woolly mammoth” means, to a human brain, something more like time. It might mean time even more than “time” does, since a brain’s chance of holding any span of years is laughable. Few bodies have felt the real pull of a century and fewer brains can grasp ten, even in dreams. What, asks the brain, is tangible in one hundred years, let alone a century repeated four hundred times?

And so a frozen mammoth means more than one gray, unspined back on a slab in a cave, rounded feet pointing at the ice-roof. More than sliding a gloved palm under that fiery wool and more than patting that trunk where it curves, as if in trumpet. More than running a glove along that corkscrewed flank to find a large and peculiar gash, made by—what did that? Not teeth or claw, but some sort of serrated tool—the kind held in a fleshy palm and steadied by an opposable thumb.

Of all the images that make our world, animal images are particularly buried inside us. We feel the pull of them before we know to name them, or how to even fully see them. It is as if they are always waiting, crude sketches of themselves, in the recesses of our bodies. As if every animal a human brain has ever seen, it has swallowed. We find their outlines, as if on Ouija boards, in mountains and in clouds. We scratch the arcs of their trunks in the dirt with our feet, or use the sharpest tools available to dig them from shocks of wood. Give us a stick and we’ll draw them. Find a discarded antler on the steppe and we’ll locate them in its tines. Hit a rock on a cave wall until it yields one. Spread them out across the night sky and we’ll point upward. See how they twinkle as they move?

Up from the mummy on that ice-cave slab comes a linked chain of animals, all of them pointing backward. That spineless knot of feet and fur untwists into an upright beast with movable legs and an intact, champing maw. She reinflates inside the humans that touch her as a circus pachyderm or an elephantine nursery toy. Further inward still, she is the image of a cutout suspended over a bassinet for eyes too new to focus, the curves and lines of her paper feet trotting at the ends of the wires. And perhaps the red-haired mammoth, which someone in the cave named Yuka, takes the onlookers further back still, to memories buried not in the brain, but in marrow and fiber and peptide. Far into the flesh, where the temporal world starts to wobble a bit.

Thirty-nine thousand years ago, young Yuka set off running. She could have run for her natural life—the land, as it was then, gave her the space to do so. She might have traveled the entire length of the steppe, had she wanted to. If she’d headed east out of what wasn’t yet Yukagir, she could run to what wasn’t yet Fairbanks. There was no ocean to stop her and barely any trees, just the hardscrabble forbs she yanked from the permafrost with that custom-made fist in her trunk. Or she could have run south for twice that distance—alone or in packs, always traveling, feet visible in the speed-reel of passing millennia as fuzzy blurs of motion. Eight thousand miles of dodging deadly silt bogs and the canny lions that followed her, growing hungrier as they, too, ran down eight thousand miles of cold. Not the same lions as now, exactly, but still leonine and speedy-moving things. Still the same sun, though brighter in the frigid sky. Still a continent, but one triple the size, its land sitting on half the planet like a fat cave bear.

And all around the lip of the steppe ran an impossible mix of fauna. A near-bestiary moving over what was not yet Europe: reindeer and hyena, bear and lion, jungle leopard and arctic fox. All the imaginable animals running alongside her, following those rivers that cut soft, deep caves through miles of limestone. Past things we now call meadows and things that were not yet ponds and things that, in essence, were men.

A silent hunter crouches in an up-jump of the steppe. More than any physical act—fighting, teaching, sleep—hi

s life is spent watching animals. Survival is hiding his soft human body and clocking the heartier megafauna as they move and mate and perish. Imagine the detail he holds inside himself after a lifetime of fiery looking. Then think of five thousand such lifetimes, all spent on that steppe and at this pitch of watching. Good God, what that amount of witness must do to a human’s insides.

To be human on the steppe was to hold a codex of every muscle in a lion’s neck, a bison’s spine, a caballine flank running to safety. Before it became anything else, a human brain was first an almanac of living shapes changing in the passing light: living shapes in the chaos of estrus, the lurch of paucity, the freeze of death. How could a creature hold such continental knowledge—generations of it—and not feel it seeping into his blood and bones and muscles? How many generations of hunters pass by before such watching troubles a hunter’s body into hysteria, or drunkenness—the animal shapes thrumming so hard at his ribcage that he must seek release outside himself?

When the red-blonde mammoth runs into eyeshot, the hunter tenses. Her wool in the rising sun seems as if it might catch fire. She’s grown enough to have her own space in the herd, but still young enough to be toppled, and as she moves, it is easy to see that her rhythm is off. That rhythm tells the hunter of the predators that got to her first. She turns to charge the lion that chases her, but only manages one belabored stamp of her thick, round foot before panicking. The mammoth turns to keep running, and her foot snaps; soon the leg will give.

Go now, thinks the hunter, imagining himself into the lion’s body, and the lion seems to listen to him. It springs sideways onto the mammoth’s back—the first bite, at her tail, is enough. The deep scratches it leaves along her sides will have no time to heal. She wrenches her fiery blonde neck, twisting herself away from the bite, and falls with a little thud.

And now it is time for the human hunter to make good on all his watching. To move forward—not running, but with firm and even paces: arm up, weapon out. He must bluff the lion into retreating. It’s a move the hunter has stolen from the lion itself after years together on the steppe. To steal from the lion, he becomes the lion. Go now, he says again—to his own body this time. He finds the rhythm of the lion inside him and brings it forward.

The lion runs away, its four feet a tawny blur. The hunter knows how little time it takes for a lion to remember its power, so the work here is quick: a hand on the mammoth’s still-hot flank and a sharp edge dug into her spine. He pulls only the most useful parts from her: vertebrae, organs, the fat and meat from her legs. For some reason, he extracts the skull, but does not take it with him. He buries it, and what else is left, into the steppe to return to later. At this point in time, he has no idea how much later that will be.

That gash on Yuka’s back is thirty-four thousand years older than the first version of Stonehenge. It’s thirty-three thousand years before anything resembling writing, and at least thirty millennia before beer, knitting, money, or apiaries. Yuka’s sharp wound is nearly as old as the bone flutes recently dug from German rock—the ones that can whistle the pentatonic sounds of birds in the changing sky—and the lion-headed man that someone carved from a mammoth tusk and abandoned in a cave for forty millennia. Fifteen thousand years after Yuka, mammoth bones will make the first huts and fences and graveyards. The architecture of Europe will be born from the bodies of the mammoths that the first hunters spent eternities watching.

Thirteen millennia after Yuka, a woman—the first known shaman—will lie in a grave with a fox in her arms. Above her body, they’ll cross two mammoth scapulae and dust the bones with yellow-red ochre. Around her, they’ll bury a collection of clay—the first known ceramics—fired into dog shapes, bear shapes, horse shapes, and also the shapes of mammoths.

Around the same time—if there is even any reason to call this “time”—a hunter will walk to a river cave, alone. Though he’s watched animals all his life, he won’t hunt them today. Instead, he will search for a giant limestone arch—sturdy and thick on one end, the other end a rounded crag with a narrower offshoot. The arch looks like a mammoth leaping over the river, from rock to rock.

Go now. Go and collect them. Collect them all in a cave hidden by a river, under a leaping mammoth of limestone, where the floor goes five hundred years between sets of footprints. Collect the lion, the rhinoceros, the ibex, the aurochs. The cave bear and the lion and the wolf. Collect them in charcoal and ochre on the sharpened ends of pine boughs. But put the largest animals—the ones held inside the hunters with the deepest-reaching memories—way in the back of the cave. Keep them far from the sunlit art of the carvers and engravers who mold stone and wood into utile things. Find them in the way-back darkness where giant bears go to die.

He walks inside the cave and lights a bough to see what he can gather. There is no space between himself and the ten millennia of his imagination. No distance between the beasts of the outside world and the beasts inside him. The back chamber is tight enough that its air is poisoned by the sighs of tree roots above him. The animals are in his short breath, in the wet tips of his fingers. As the lamplight ripples past the rock, there are lions in the fire.

He puts a hand to that soft wall and there she is, running for eight thousand years. And he becomes the mammoth so he can envision the mammoth, running toward his hand so fast her feet are rounded blurs at the ends of her triangle legs. His palm on the rock and her red fur, the thrum of his heart and the roll of her feet. Their feet. The black of the fire and the black of the bough and the red ochre that frames them both like fur. Their trunk pulling downward and the charcoal gash running the middle of their back. Their brown hand palpitating it all in the limestone, then pulling away.

He has found the mammoth in the rock.

Therefore to a man that is suddenly still, and leaveth to speak, it is said, Lupus est in fabula: “The wolf is in the tale.”

Bartholomaeus Anglicus, On the Nature of Things

WINTERS WERE EVIL in Gubbio. The town was shoved into the lowest spur of a mountain, faced by warring neighbors and terrible winds. The citizens peered from their guard towers into the darkness, beyond the high walls and past the amphitheater that had been moldering near them for a thousand years. They were starving, but did not hunt in their pine forests on account of the Wolf.

This was also the name given to their famine and their plague: lupus, the hungry devil always within walking distance of their city gates. For hunger, like the Wolf, takes from you what it needs, and does so with remorselessness and skill. But there were some occasions that evil winter when the people of Gubbio had no choice but to leave the town. Their dead were always buried outside those gates, since the time of the amphitheater, Wolf or no.

A posse comitatus of men and dogs dragged the latest bodies past the empty fields—the sheep and shepherds gone now—and into the frigid woods where they knew the Wolf would find them. They knew of his night vision and his cocky howl. They knew how well he chased less nimble beasts in the deep snow. They knew that, on bright afternoons, he’d make sport with shepherd boys and then return at twilight to pull them back to his cave. The books said twilight was the time of the Wolf, as the beast devoured the setting sun.

Learned men had kept track of the nature of things since the time of their amphitheater. Their books told of how, in lean seasons, the Wolf ate wind and how he sometimes gobbled mud so he could topple a stag with his weight. They wrote that he cooked the flesh he killed with his hot, acidic breath. If, they said, when stalking, he stepped on a twig and alerted the innocent lamb, he bit his guilty foot as punishment. Here he is, a whole page in the Bestiarium vocabulum, sulking in vivid color. Note how the Wolf holds his right paw between his own pointed teeth.

Mostly, the books of beasts used the Wolf to illustrate the most lupine of human sins. You must hate the sins of the Wolf, the bestiaries said—the sins of rogues, apostates, and highwaymen—as they are sins too cunning to simply be feared. Hear these words on the Wolf, sinners, and then think

upon the Wolf that might, at any moment, ravage the Lamb inside you.

Up in the woods, the Wolf watched them in the half-light while standing on a frozen grave. He sniffed the air and turned toward the approaching men, even though the bestiaries said wolves could not turn their heads at all—just as the Devil is unable to turn toward righteousness. But the Wolf that came to Gubbio did swivel its head to see them, which gave the men horrific pause.

It is written that, when man and Wolf meet, should the Wolf see the man first, the man will fall mute. On one colorful page of the bestiary, the Wolf is ochre and looks no more than a dog. It sneaks up behind a man in a russet tunic; the man holds his hand at his own white chin. If the dumbstruck man survives this encounter—perhaps he will be the only one of his group to do so—the books say his voice may return, but only after he strips naked and claps together two loud stones.

Francesco di Pietro di Bernardone was nearly naked when he arrived in Gubbio. He’d left Assisi in a cast-off cloak, but highwaymen robbed him of it before he reached Valfábbrica. That town was troubled by flood and did not welcome him. In Gubbio, however, he had old friends from the war. They led him in, found him a tunic, told him they’d had no flood. But we do have a wolf, they said, and Francis fell silent with prayer.

The men Francis knew in Gubbio noticed great changes in him. They could not decipher it; where before, he was dandy and hot-blooded, now he curled up in the corner, gaunt and still. He swallowed ash before meals to keep himself from savoring food. When his flesh buzzed with pleasure, he jumped into thorny bushes, or retreated to fast in a cave. Comfort was slipping from him like color from a sick girl’s face. Francis had willingly let the hunger crawl into his life.

Gubbio’s gates opened for him again and he walked out. His soldier-fellows and their dogs followed behind with axes, heading past the amphitheater and up into the woods, where the brush was thick. Soon, though, fear froze them and they were unable to advance. Only Francis, in his thin tunic and rotten shoes, walked on.

Animals Strike Curious Poses

Animals Strike Curious Poses